Project Description

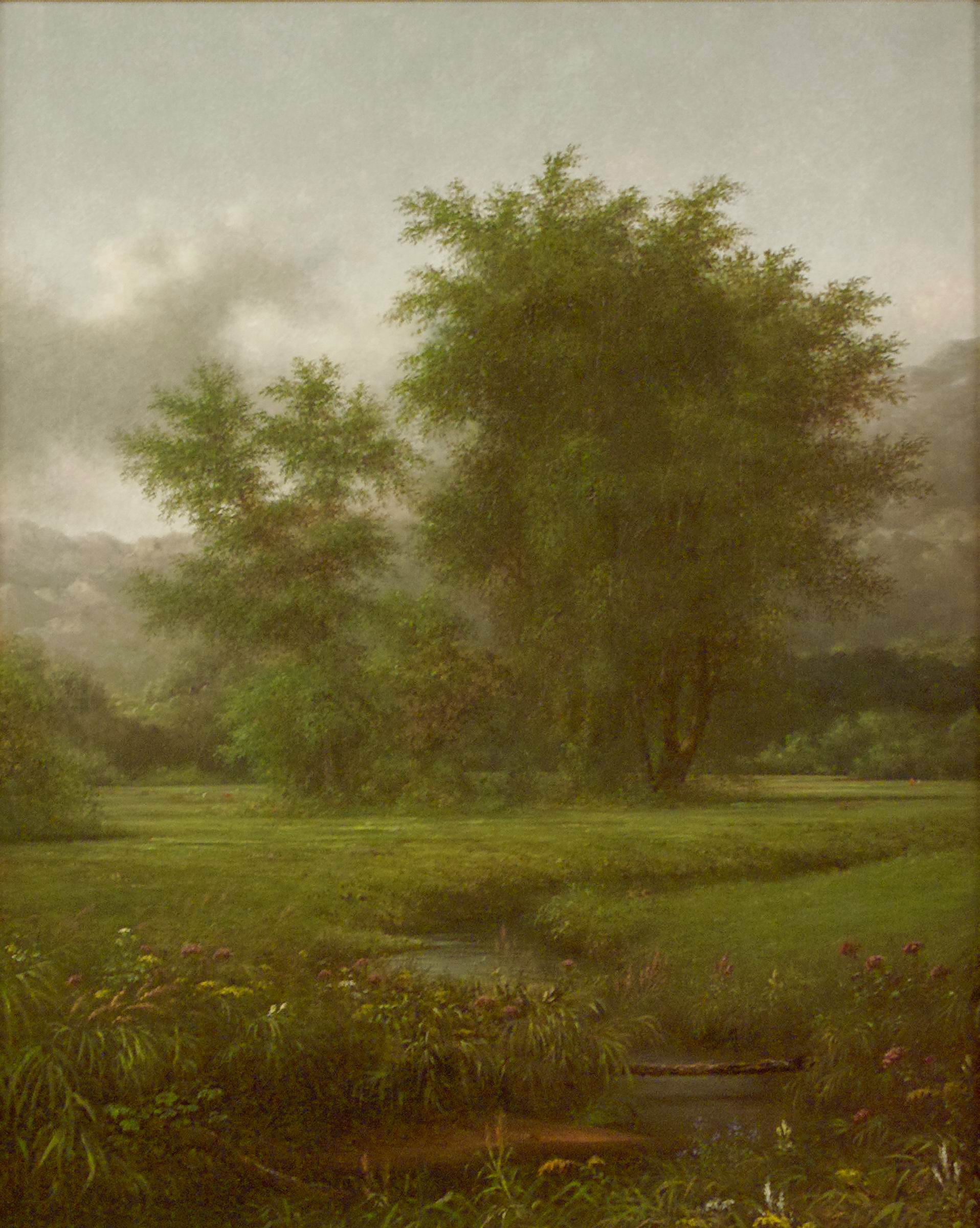

Martin Johnson Heade

Valley in the White Mountains, 1861

Oil on canvas

21 x 17 inches

Signed and dated lower left: MJHeade 61

Provenance

Dr. Elton Yasuna, Worcester, Massachusetts

By descent in the Yasuna family

Hirschl & Adler Gallery, New York, 1988

Exhibitions

“The Art of Collecting,” Danforth Museum, Framingham, Massachusetts, September 13-November 29, 1981.

Literature

Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., The Life and Work of Martin Johnson Heade: A Critical Analysis and Catalogue Raisonné, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000, No. 85, p. 220 (illus. in black and white).

Essay

No American landscape painter of the mid-nineteenth century excelled Martin J. Heade in capturing the effects of moisture-laden atmospheres. From almost his earliest attempts at landscape, Heade was fascinated with the soft yet often eerie luminescence of Eastern coastal fogs, of the tropical humidity of Brazil and the Caribbean, of upland showers and marshland mists. Even when Heade was capturing the electric clarity and threatening gloom of an approaching thunderstorm, it was always in the context, and knowledge, of the deluge that would inevitably follow.

In this preoccupation, Heade’s landscapes stand out quite vividly from those of his contemporaries and competitors, like Sanford R. Gifford, Frederic Edwin Church and John F. Kensett. The one American artist who perhaps comes closest to Heade in his subtlety of atmospheric effects is Fitz Hugh Lane, whose paintings Heade had seen and studied in Boston. Yet Lane, even at his “foggiest,” still distances himself, and the viewer, from any sense of intimacy (and its implied threat of uncertainty and confusion) with his precise drawing and careful compositional geometries. Heade, in contrast, almost always opts for sparer, more asymmetrical and more informal designs, which are no less filled with telling detail, yet almost always place the viewer in the midst of the picture, rather that at some discretely appointed – and pictorially controlled – distance.

As early as 1860 Heade was experimenting with marshland scenes, which he painted at precisely those transitional moments when the sun was rising or setting, and thus also at those moments when atmospheric moisture was most likely to be either dissipating or accumulating. Anyone who has traveled the East Coast of the United States of an early summer morning, from Grand Manan and the Androscoggin to the Shenandoah and the Blue Ridge, has also witnessed the magical effects of lifting fog, whose shrouds and wisps can still be found clinging to the hillsides at mid-morning.

In the summer of 1860 Heade embarked on a sketching trip through northern New England, stopping first in Brattleboro, Rutland, and Burlington, Vermont, and then moving on to the St. Lawrence River, from where he journeyed south through New Hampshire and western Maine in July and August. At first he was not impressed with the scenery, finding that it failed to resonate with the landscape themes that he was most interested in portraying. Although he made numerous sketches over the course of his summer tour, they resulted in only three completed works, two of which remain lost to the historical record. Indeed, the only surviving painting from that summer-long, and, in many ways, pivotal trip is Valley in the White Mountains.

With its vertical format, precise foreground detail, lush valley foliage, and mountainous backdrop, Valley in the White Mountains is indeed atypical when compared with much of Heade’s later oeuvre. It should be remembered, however, that it was precisely at this point in his career, in the first few years of the 1860s, that Heade was at his most ambitious and explorative. Within a few years, he would settle on the themes that made him famous, but between 1858 and 1862 he was still in the process of determining an artistic direction.

Just as he would emulate Frederic Church in his early sunset pictures, Heade seems here, in Valley in the White Mountains, to be looking to the example of William Trost Richards and other artists of the American Pre-Raphaelite movement for inspiration. The foreground of the painting is wonderfully detailed in its multitude of botanically correct, and identifiable, blossoms, and the meandering valley brook, midground cluster of noble trees, and distant rising peaks complete a classic late Hudson River composition. There is even a fallen log across the brook, suggesting another mode of passage, though it seems on second glimpse to be too frail to support a human’s weight.

That delicacy of effect, combined with the gentle, pastoral scenery, and the softening effects of morning dew and fog, tell us immediately that we have entered an entirely different world from that of either the classic Hudson River landscape painters, the American Pre-Raphaelites, or their contemporaries, the Luminists.

Seven years after he painted Valley in the White Mountains, Heade painted a wonderfully suggestive and, again, “anomalous” painting titled April Showers (1868; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), which depicts an apple orchard in blossom under a dark, cloudy and rain-filled sky. As Ted Stebbins, Heade’s biographer, notes, in words that could as easily be applied to Valley in the White Mountains,

April Showers tests the boundaries of Hudson River School practice. True, this painting celebrated nature, but it did so through color and by means of the subtlest depiction of cloudy skies and falling rain the artist had yet achieved. Church, Bierstadt, and other leading painters usually exalted the earth by emphasizing the grandeur of its geologic and living forms, its mountains and lakes, its tall pines and ancient oaks.

In April Showers

Bruce W. Chambers, Ph.D.